|

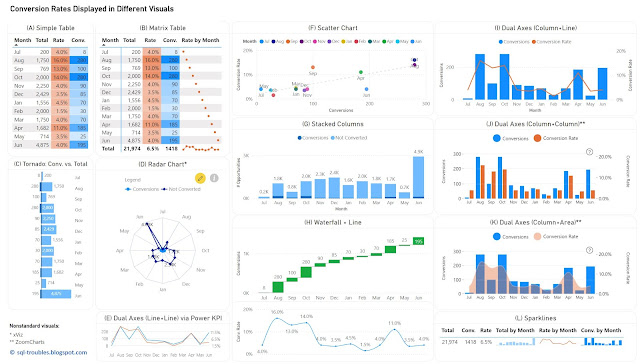

| Graphical Representation Series |

Introduction

Conversion rates record the percentage of users, customers and other

entities who completed a desired action within a set of steps, typically as

part of a process. Conversion rates are a way to evaluate the performance of

digital marketing processes in respect to marketing campaigns, website traffic

and other similar actions.

In data visualizations the conversion rates can be displayed occasionally alone over a time unit (e.g. months, weeks, quarters), though they make sense only in the context of some numbers that reveal the magnitude, either the conversions or the total number of users (as one value can be calculated then based on the other). Thus, it is needed to display two data series with different scales if one considers the conversion rates, respectively display the conversions and the total number of users on the same scale.

For the first approach, one can use (1) a table or heatmap, if the number of values is small (see A, B) or the data can be easily aggregated (see L); (2) a visual with dual axis where the values are displayed as columns, lines or even areas (see E, I, J, K); (3) two different visuals where the X axis represents the time unit (see H); (4) a visual that can handle by default data series with different axis - a scatter chart (see F). For the second approach, one has a wider set of display methods (see C, D, G), though there are other challenges involved.

|

| Conversion Rates in Power BI |

Tables/Heatmaps

When the number of values is small, as in the current case, a table with the unaltered values can occasionally be the best approach in terms of clarity, understandability, explicitness, or economy of space. The table can display additional statistics including ranking or moving averages. Moreover, the values contained can be represented as colors or color saturation, with different smooth color gradients for each important column, which allows to easily identify high/low values, respectively values from the same row with different orders of magnitude (see the values for September).

In Power BI, a simple table (see A) allows to display the values as they are, though it doesn't allow to display totals. Conversely, a matrix table (see B) allows to display the totals, though one needs to use measures to calculate the values, and to use sparklines, even if in this case the values displayed are meaningless except the totals. Probably, a better approach would be to display the totals with sparklines in an additional table (see L), which is based on a matrix table. Sparklines better use the space and can be represented inline in tables, though each sparkline follows its own scale of values (which can be advantageous or disadvantageous upon case).

Column/Bar Charts

Column or bar charts are usually the easiest way to encode values as they represent magnitude by their length and are thus easy to decode. To use a single axis one is forced to use the conversions against the totals, and this may work in many cases. Unfortunately, in this case the number of conversions is small compared with the number of "actions", which makes it challenging to make inferences on conversion rates' approximate values. Independently of this, it's probably a good idea to show a visual with the conversion rates anyway (or use dual axes).

In Power BI, besides the standard column/bar chart visuals (see G), one can use also the Tornado visual from Microsoft (see C), which needs to be added manually and is less customizable than the former. It allows to display two data series in mirror and is thus more appropriate for bipartite data (e.g. males vs females), though it allows to display the data labels clearly for both series, and thus more convenient in certain cases.

Dual Axes

A dual-axis chart is usually used to represent the relationship between two variables with different amplitude or scale, encoding more information in a smaller place than two separate visuals would do. The primary disadvantage of such representations is that they take more time and effort to decode, not all users being accustomed with them. However, once the audience is used to interpreting such charts, they can prove to be very useful.

One can use columns/bars, lines and even areas to encode the values, though the standard visuals might not support all the combinations. Power BI provides dual axis support for the line chart, the area chart, the line and staked/clustered column charts (see I), respectively the Power KPI chart (see E). Alternatively, custom visuals from ZoomCharts and other similar vendors could offer more flexibility. For example, ZoomCharts's Drill Down Combo PRO allows to mix columns/bars, lines, and areas with or without smooth lines (see J, K).

Currently, Power BI standard visuals don't allow column/bar charts on both axes concomitantly. In general, using the same encoding on both sides of the axes might not be a good idea because audience's tendency is to compare the values on the same axis as the encoding looks the same. For example, if the values on both sides are encoded as column lengths (see J), the audience may start comparing the length without considering that the scales are different. One needs to translate first the scale equivalence (e.g. 1:3) and might be a good idea to reflect this (e.g. in subtitle or annotation). Therefore, the combination column and line (see I) or column and area (see K) might work better. In the end, the choice depends on the audience or one's feeling what may work.

Radar Chart

Radar charts are seldom an ideal solution for visualizing data, though they can be used occasionally for displaying categorical-like data, in this case monthly based data series. The main advantage of radar charts is that they allow to compare areas overlapping of two or more series when their overlap is not too cluttered. Encoding values as areas is in general not recommended, as areas are more difficult to decode, though in this case the area is a secondary outcome which allows upon case some comparisons.

Scatter Chart

Scatter charts (and bubble charts) allow by design to represent the relationship between two variables with different amplitude or scale, while allowing to infer further information - the type of relationship, respectively how strong the relationship between the variables is. However, each month needs to be considered here as a category, which makes color decoding more challenging, though labels can facilitate the process, even if they might overlap.

Using Distinct Visuals

As soon as one uses distinct visuals to represent each data series, the power of comparison decreases based on the appropriateness of the visuals used. Conversely, one can use the most appropriate visual for each data series. For example, a waterfall chart can be used for conversions, and a line chart for conversion rates (see H). When the time axis scales similarly across both charts, one can remove it.

The Data

The data comes from a chart with dual axes similar to the visual considered in (J). Here's is the Power Query script used to create the table used for the above charts:

let Source = #table({"Sorting", "Month" ,"Conversions", "Conversion Rate"} , { {1,"Jul",8,0.04}, {2,"Aug",280,0.16}, {3,"Sep",100,0.13}, {4,"Oct",280,0.14}, {5,"Nov",90,0.04}, {6,"Dec",85,0.035}, {7,"Jan",70,0.045}, {8,"Feb",30,0.015}, {9,"Mar",70,0.04}, {10,"Apr",185,0.11}, {11,"May",25,0.035}, {12,"Jun",195,0.04} } ), #"Changed Types" = Table.TransformColumnTypes(Source,{{"Sorting", Int64.Type}, {"Conversions", Int64.Type}, {"Conversion Rate", Number.Type}}) in #"Changed Types"

Conclusion

Upon case, depending also on the bigger picture, each of the above visuals can be used. I would go with (H) or an alternative of it (e.g. column chart instead of waterfall chart) because it shows the values for both data series. If the values aren't important and the audience is comfortable with dual axes, then probably I would go with (K) or (I), with a plus for (I) because the line encodes the conversion rates better than an area.

Happy (de)coding!