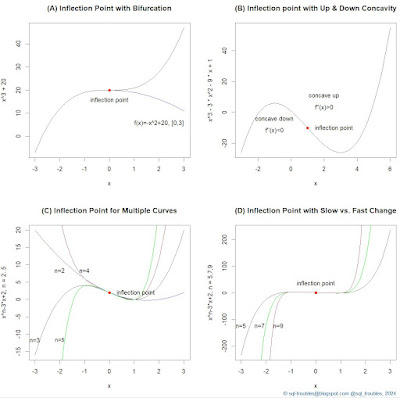

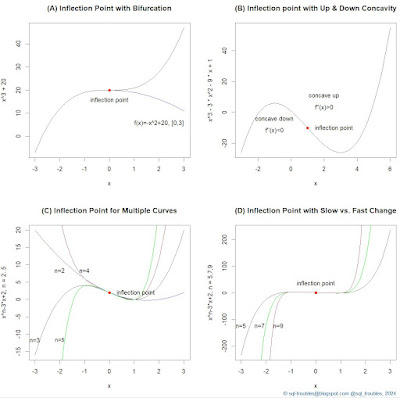

For a previous post on inflection points I needed a few examples, so I thought to write the code in the R language, which I did. Here's the final output:

|

| Examples of Inflection Points |

And, here's the code used to generate the above graphic:

par(mfrow = c(2,2)) #2x2 matrix display

# Example A: Inflection point with bifurcation

curve(x^3+20, -3,3, col = "black", main="(A) Inflection Point with Bifurcation")

curve(-x^2+20, 0, 3, add=TRUE, col="blue")

text (2, 10, "f(x)=-x^2+20, [0,3]", pos=1, offset = 1) #label inflection point

points(0, 20, col = "red", pch = 19) #inflection point

text (0, 20, "inflection point", pos=1, offset = 1) #label inflection point

# Example B: Inflection point with Up & Down Concavity

curve(x^3-3*x^2-9*x+1, -3,6, main="(B) Inflection point with Up & Down Concavity")

points(1, -10, col = "red", pch = 19) #inflection point

text (1, -10, "inflection point", pos=4, offset = 1) #label inflection point

text (-1, -10, "concave down", pos=3, offset = 1)

text (-1, -10, "f''(x)<0", pos=1, offset = 0)

text (2, 5, "concave up", pos=3, offset = 1)

text (2, 5, "f''(x)>0", pos=1, offset = 0)

# Example C: Inflection point for multiple curves

curve(x^3-3*x+2, -3,3, col ="black", ylab="x^n-3*x+2, n = 2..5", main="(C) Inflection Point for Multiple Curves")

text (-3, -10, "n=3", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^2-3*x+2,-3,3, add=TRUE, col="blue")

text (-2, 10, "n=2", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^4-3*x+2,-3,3, add=TRUE, col="brown")

text (-1, 10, "n=4", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^5-3*x+2,-3,3, add=TRUE, col="green")

text (-2, -10, "n=5", pos=1) #label curve

points(0, 2, col = "red", pch = 19) #inflection point

text (0, 2, "inflection point", pos=4, offset = 1) #label inflection point

title("", line = -3, outer = TRUE)

# Example D: Inflection Point with fast change

curve(x^5-3*x+2,-3,3, col="black", ylab="x^n-3*x+2, n = 5,7,9", main="(D) Inflection Point with Slow vs. Fast Change")

text (-3, -100, "n=5", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^7-3*x+2, add=TRUE, col="green")

text (-2.25, -100, "n=7", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^9-3*x+2, add=TRUE, col="brown")

text (-1.5, -100, "n=9", pos=1) #label curve

points(0, 2, col = "red", pch = 19) #inflection point

text (0, 2, "inflection point", pos=3, offset = 1) #label inflection point

mtext("© sql-troubles@blogspot.com @sql_troubles, 2024", side = 1, line = 4, adj = 1, col = "dodgerblue4", cex = .7)

#title("Examples of Inflection Points", line = -1, outer = TRUE)

Mathematically, an inflection point is a point on a smooth (plane) curve at which the curvature changes sign and where the second derivative is 0 [1]. The curvature intuitively measures the amount by which a curve deviates from being a straight line.

In example A, the main function has an inflection point, while the second function defined only for the interval [0,3] is used to represent a descending curve (aka bifurcation) for which the same point is a maximum point.

In example B, the function was chosen to represent an example with a concave down (for which the second derivative is negative) and a concave up (for which the second derivative is positive) section. So what comes after an inflection point is not necessarily a monotonic increasing function.

In example C are depicted several functions based on a varying power of the first coefficient which have the same inflection point. One could have shown only the behavior of the functions after the inflection point, while before choosing only one of the functions (see example A).

In example D is the same function as in example C with varying powers of the first coefficient considered, though for higher powers than in example C. I kept the function for n=5 to offer a basis for comparison. Apparently, the strange thing is that around the inflection point the change seems to be small and linear, which is not the case. The two graphics are correct though, because as basis is considered the scale for n=5, while in C the basis is n=3 (one scales the graphic further away from the inflection point). If one adds n=3 as the first function in the example D, the new chart will resemble C. Unfortunately, this behavior can be misused to show something like being linear around the inflection point, which is not the case.

# Example E: Inflection Point with slow vs. fast change extended

curve(x^3-3*x+2,-3,3, col="black", ylab="x^n-3*x+2, n = 3,5,7,9", main="(E) Inflection Point with Slow vs. Fast Change")

text (-3, -10, "n=3", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^5-3*x+2,-3,3, add=TRUE, col="brown")

text (-2, -10, "n=5", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^7-3*x+2, add=TRUE, col="green")

text (-1.5, -10, "n=7", pos=1) #label curve

curve(x^9-3*x+2, add=TRUE, col="orange")

text (-1, -5, "n=9", pos=1) #label curve

points(0, 2, col = "red", pch = 19) #inflection point

text (0, 2, "inflection point", pos=3, offset = 1) #label inflection point

Comments:

(1) I cheated a bit calculating the second derivative manually, which is an easy task for polynomials. There seems to be methods for calculating the inflection point, though the focus was on providing the examples.

(2) The examples C and D could have been implemented as part of a loop, though I needed anyway to add the labels for each curve individually. Here's the modified code to support a loop:

# Example F: Inflection Point with slow vs. fast change with loop

n <- list(5,7,9)

color <- list("brown", "green", "orange")

curve(x^3-3*x+2,-3,3, col="black", ylab="x^n-3*x+2, n = 3,5,7,9", main="(F) Inflection Point with Slow vs. Fast Change")

for (i in seq_along(n))

{

ind <- as.numeric(n[i])

curve(x^ind-3*x+2,-3,3, add=TRUE, col=toString(color[i]))

}

text (-3, -10, "n=3", pos=1) #label curve

text (-2, -10, "n=5", pos=1) #label curve

text (-1, -5, "n=9", pos=1) #label curve

text (-1.5, -10, "n=7", pos=1) #label curve

Happy coding!

Previous Post <<||>> Next Post

References:

[1] Wikipedia (2023) Inflection point (link)